My developing interest in Shanghai’s history especially the Indian side had very little clues to fall back on initially. Only few Parsi opium merchants(Readymoney, Jeejibhai) who had made their fortunes in the China trade have been highlighted in British China-British India history. So, it was quite a surprise when I chanced upon Dr Lalkaka’s name.

He was a resident of Shanghai since 1886, having joined his uncle B.P.Lalkaka, an established businessman. The Parsi community in quasi-colony of British’ Shanghai’s International Settlement was growing and, it was evident they were the preferred trading class in India and definitely so in China. They were able to mingle with the British rulers more easily than any other Indians. Mannerisms, appearance may have played a part as well.

Dr. Lalkaka, who studied medicine in Bombay and England would join the Shanghai Volunteer Corps as a private. From Arnold Cartwright’s book Twentieth Century Impressions of Hong Kong, Shanghai…Volume 1′ :

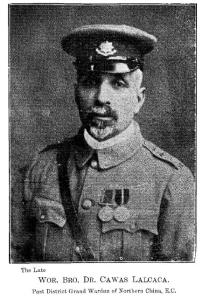

“SURGEON MAJOR CAWAS LALCACA was at Bombay in 1862 and educated in and London where he qualified as a of Medicine and as a Licentiate of the College of Physicians He came to Shanghai in 1886 and joined A Company the Shanghai Volunteers as a private in following year. In 1891 he was promoted to the medical staff as surgeon lieutenant becoming surgeon captain in 1896 and principal medical officer to the corps in 1907, being granted the rank of major in 1908.”

Lalkaka led a somewhat quiet life. Clearly, based on publications of the time, he was a model citizen with unblemished record except when his clients/patients didn’t pay his fees. But his membership in the Shanghai Masonic society was the first indication I had of the society’s influence in the Far East. How did a doctor end up in this fraternal organization of ‘grand lodges?’ Well, the answer, after much digging led me to Royal Sussex Lodge, No. 501 and Northern Lodge of China, No. 570, E.C. where Dr. Cavas Lalkaka was an eminent member. His uncle, Bapujee P Lalkaka and another family member Eduljee P Lalkaka had most likely wielded tremendous influence since they had been Freemasons much before their nephew became one. Even in Hong Kong many Parsis were part of Freemasonry. As such, only affluent and prominent men were members of the Masonic society in the Far East. (Click this link to understand how Freemasonry came to China)

But, then Dr. Lalkaka took a sabbatical and arrived in London – maybe he intended to pursue opportunities here? One has to assume so as there are no records on his journey to London except in one of the Royal Sussex Lodge 501 meetings stating he would be in London for a year and would then be back in Shanghai afterward.

Dr Lalkaka never returned to Shanghai. Indian freedom activist Madan Lal Dhingra was in London at the same time. On 1 July 1909, Dhingra attended an ‘At Home’ hosted by the National Indian Association at the Imperial Institute. At the end of the event, as the guests were leaving, Dhingra shot Sir Curzon-Wyllie, an India Office official, at close range. His bullets fatally hit Dr Lalkaka as well, also an invitee. Lalkaka had attempted to stop Dhingra but was shot accidentally. Dhingra, later expressed regret for shooting Lalkaka who was never the intended victim in his plans.

In keeping with the Parsi faith and rites in Britain, Dr. Lalkaka was buried in Parsi section of the Brookewood cemetery (and his grave is still here). His funeral was well attended by the Parsi community members and British officials. Dr Lalkaka was 48 years of age when he died, single and issue less. In his honor the London School of Tropical Medicine introduced an award medal for meritorious students. In the reconstructed 1912 Shanghai Masonic Lodge, in the East room a portrait of Dr Lalkaka above the paneling was exhibited with a brass plate underneath recording the Masonic life of the distinguished Brother Lalkaka and his tragic death. In Shanghai Henry Lester’s hospital (today’s Renji hospital) Lalkaka’s bust statue was erected in its premises.

The death of Sir Curzon-Wyllie received international condemnation (and praise) and even Mahatma Gandhi denounced the assassination. Dhingra was sentenced to death. The Masonic society in Shanghai including the Royal Sussex Lodge 501 mourned Lalkaka’s loss.

Dr Lalkaka’s grave in Brookwood cemetery, UK

Dr Lalkaka became a victim inadvertently and consequently a post script in British and Indian history. But, Dr Lalkaka has remained much submerged under the layers of cloaked and at times invisible Shanghai-Indian history. Even today, historians haven’t mentioned the Dhingra incident nor Dr. Lalkaka’s connection when referring to Shanghai’s checkered and colorful past. A pity.

4 Responses »