Photographs, in absence of substantial narratives help retrieve forgotten histories. With Shanghai Sikhs, the images are plenty and offer vital clues but sometimes you just have to peek over Shanghai’s shoulder to judge the context of the visual content. In Malaysia, Singapore , Burma, Sikhs were engaged in the British army or police and a odd picture of them here, a skimpy fact there help straighten a very potholed Shanghai Sikh narrative.

The British replicated their police and army system in the colonies and a handy blueprint was utilized in various corners of the empire. Quite like the modern fast food franchises. Try going to McDonalds. The layout is same everywhere. The menu too…only few local elements make it different , I would imagine. For instance, in India, McDonalds offers tandoori style chicken nuggets . At least it did couple of years ago…The same theory applied to the British raj…engineer the “Tommy” framework, bring in the “natives”, some Sikhs, then just throw in a reference here to the local language and a custom there and voila… hail the McDonald look of the British raj!

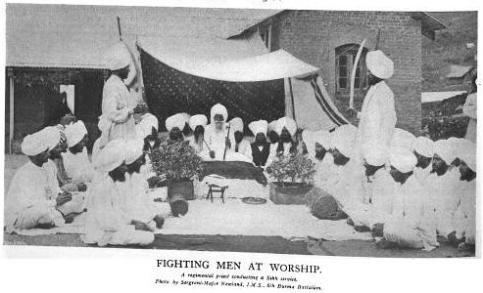

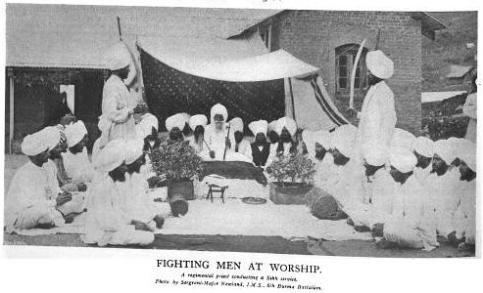

Above is a picture of a Sikh regiment in Burma praying to the holy book, Guru Granth Sahib. In pristine white, praying, perhaps imagining what it would be like back home in their local holy gurdwara.

In British wars in the colonies, the Sikhs , in absence of a Sikh temple would have worshipped out in the open, put some borrowed, potted flowers in bloom on either side of the temporary dais, two soldiers holding the talwar would stand guard and others would sit, legs folded on a sheet or rug.. The granthi who was attached to the regiments would drape a raised dais in decorative silk folds, and depending on the time of the days, keertans followed by the ceremonial robust shout celebrating the Wahe Guru would have rung the air. It must have been a splendid sight.

Some Opium war/Boxer uprising visual narratives hint a similar happening in China. Then, of course one has to rely on bare bones that help conjure the image of a Shanghai Sikh praying out in the open, much before a gurdwara was opened, perhaps it was in a little house or in the police barracks where the festivals, like Guru Nanak’s birth celebrations took place, among other fellow Sikhs, reminiscing of good times back in Punjab with family and friends.

Sometimes a picture can say so much and other times one has to trek the McDonald path that the Shanghai Sikh sojourners like their fellowmen in the colonies would have undertaken to retrieve their lost stories. One that left a strong British whiff but little scent of their own.

Leave a Response »